The idea of branding – and indeed the term ‘branding’ itself – began thousands of years ago, when people started literally branding their livestock with hot iron as a mark of ownership or quality. Gradually through the years, the notion of branding as a clear visual symbol has evolved and spread to practically all industries. Some of the principles of branding include clarity (legible, easy-to-read even within a short time), identity (the mark should communicate the idea/spirit of the brand) and consistency (consistent style of application to reinforce the mark’s strength and recognize-ability).

These principles have generally evolved into extremely comprehensive brand identity guidelines – the exact vector of the marks notwithstanding, there are also generally stringent rules about the colors, minimum perimeter space around the logos, where and how the logo may be used, etc. Like a jewel on a crown, they were the untouchables – the identities must be so – they stand proudly on or atop products, displays, posters, etc., almost like a king watching in solitude over the rest of the artwork doing the legwork in conveying the message. The brand-mark was very much simply a stamp of approval.

Lately though, I’m beginning to see some forward-thinking brand-marks developed less as a stamp, but more as a flexible lasso to hold everything together. Wolff Olins is among the pioneers in this school of thought. As their CEO, Karl Heiselman remarks:

In the past, corporate identity was about control and consistency. With too much control, people tend to forget about content. In the era of blogging, social networking and user-generated content … a bit of flexibility is essential.

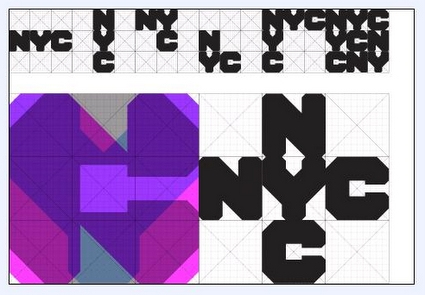

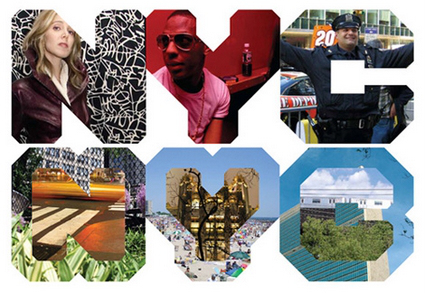

They are often just as strong and iconic (if not more), but they have an added dimensionality and freeplay that allows for creative interpretations of the symbol, rather than just a static stoic symbol. Sometimes they are used as a design tool – an example is the ‘NYC’ logo for New York City, which can be manifested beautifully such as in the second picture below:

Some other memorable and successful designs from Wolff Olins include the Sony Ericsson symbol, which is being used in place of a verb in many billboards and poster advertisements, leaving the user to imagine and associate whatever the word is (and associate that to Sony Ericsson too):

Another one is the Product(RED) campaign – the bracket and the superscript RED forms an extremely strong visual identity, and yet allows a large amount of free play to how it is used, which is especially important given the varied styles and usage for its partners.

They are also the ones behind the London 2012 Olympic logo, which I didn’t find too impressive (and blogged here). The logo was along the same thought – promising versatility and flexibility in usage – but I thought aesthetically they weren’t as well-done as some of these above.

It’s great though to see brands getting more alive and versatile. With the new mediums of expression (cellphones? Google Earth views?) and the Web2.0 culture of hacking and mashing, a versatile logo allows the audience not only to receive but also to actively reciprocate and reinterpret what these brands mean to them (such as the (LESS) campaign in response to the RED). Some marketers may freak out and take this as perversions of the company’s brand identity – but let’s face it – a brand is what the consumers think about you, and not what you want them to think about you. And with modern technologies like the net, there is no way you can stop them either. So might as well just leap in!